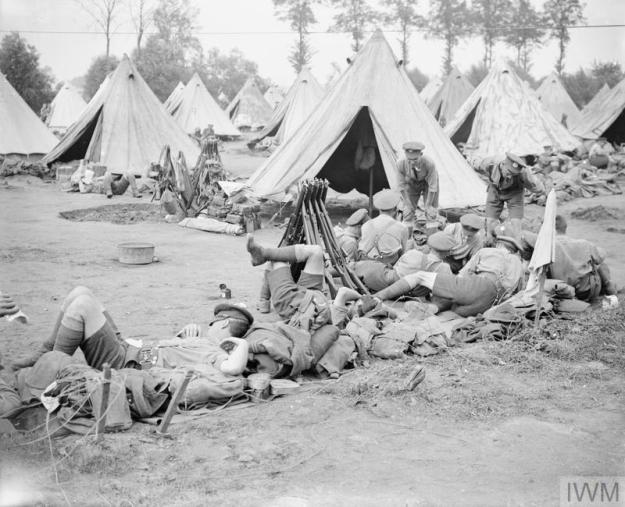

Two days after zero hour, on the morning of 2nd August 1917, the survivors of G battalion’s Tank Crews were slumped back at the La Lovie camp, exhausted after a day that had taken them to the limits of their physical and mental endurance. Most were left with a kaleidoscope of momentary images of the battlescape glimpsed through prisms and shutters. Those with the unenviable job of venturing outside to grapple with the 8-cwt unditching beam, deep in mud and exposed to shell and machine-gun fire, witnessed scenes they’d rather forget. Some tank men were forced to fight on foot, where survival was a lottery. The Tanks lay scattered across the battlefield: bogged down, broken, hit by shell fire or abandoned after making it back to the rallying points in ones and twos before dark.

Frascati Lying-up Point for Zero Hour

Start Points etc. for 31st July 1917

What had Merton’s tank man, Robert Handley, seen and done on that first day? The eye-witness testimony of Srgt. J.C. Allnatt of 19th Company, and 2 Lt D.G.Browne of 21st Company describes the confusion as the tanks negotiate awful ground, struggling to keep in contact with the infantry, individual tanks become isolated. Vulnerable to shell fire, there are miraculous escapes and terrible ends.

After reaching the lying up point at Frascati by 10.30pm on the night of the 30 July, the crews had little time before moving off again to reach their starting points for zero hour. Joseph Charles Allnatt the sergeant driver of the “Gravedigger”, Tank G10, gave his vivid account of the hours that followed in an article written in 1958. His section of tanks moved off in the fearful noise of the shrieking and bursting shells, it wasn’t long before conditions and mechanical problems played a part:

“Tanks were facing in all directions and already some were in trouble …. Each time we went into or passed through a shell hole the muddy water came sluicing into the floor of the tank, making everything into a filthy mess … I then saw the crew of one of the tanks of my Section collecting water from a shell hole with petrol cans. Their tank had a leaking radiator, and I understand that during the day they used 120 cans of water – not a very pleasant thing to have to do under fire… I retraced my way on the far side of the Steinbeek and took up the route from which I had made a diversion. I had still another half-mile to go to get to my final objective – the cemetery …. There was nothing and nobody in sight. The going was still terrible but I got to the cemetery and went alongside its battered wall. I knew that by this time I must be getting dangerously short of petrol and still had to make my way back to the rallying point at Kitchener’s Wood…. Unfortunately, at this time the other tank – “Glamorgan” I think its name was – standing still firing at the enemy, with all its guns. It was bound to happen, although they were unaware of it, enemy shells were falling all about it. I thought for a moment that I could send some-one to tell them what was happening, but I knew it would probably mean the death of one of my crew. I turned away momentarily, and when I looked back, “Glamorgan” had disappeared … We then began to get it in earnest. Our rate of travel was very slow so we were almost a sitting target. Again and again enemy shells missed us by feet, and at least one lobbed underneath us heaving us up, without doing any damage at all. All the while I steered a zig-zag course … Ever since leaving the Steinbeek and the German counter-attack the crew had given up all thought of further action and were all sound asleep on the muddy floor, with Lewis guns, spare parts and empty cases strewn around them … I heard the voice of the Adjutant.8 He poked his head in and shouted, “Who’s there.” I told him. He said “What on earth are you doing here?” I said, “Our orders are to stand by.” He said, “Well, I order you to abandon tank, and get out as quickly as you can.” Dusk was now falling and we had to cover a distance of about 1½ miles … I found a pit which had formally [sic] been a shell bunker. I flopped down … I had not been asleep more than two or three minutes, when somebody roused me with the news that we were to retire to a place called Rezenburg [sic – this should be Reigersburg] Chateau, and thence we would be conveyed back to camp. “[Extracts of Full acount]

It was dark by this time and after a hurried crossing back across the Yser canal, waiting lorries took the exhausted crews back to La Lovie camp, a slow journey on roads crammed with transport. Both the “Gravedigger” and the “Glamorgan” were part of 19th Company’s fighting tanks. Suffering a direct hit, the explosion had snuffed out the lives of eight men of Tank G10 in an instant. The names of seven of its crew members can be found on the Menin Gate. Tank commander 2nd Lt. James Walker Lynch is commemorated in St Julien Dressing Station Cemetery, where Special Memorial 1 states “Buried in this cemetery, actual grave unknown”.

2 Lt. D.G.Browne, commander of the female tank G46 “Gina”, re-lived the first day in his book the “Tank in Action”, published in 1920. He dedicated an entire chapter to the lengthy description of the first day’s fighting. It contains information which is important evidence of Robert Handley’s possible fate on 2nd August 1917.

G46 was near Canada and Hampshire Farm as they crossed, moving beyond what had been the German front line:

“Dawn had broken — a miserable grey twilight behind heavy clouds; and the creeping barrage, with its following infantry, was already far up the ridge … We had anticipated difficulties here, but the reality was worse than anything that I, for one, had imagined. The front line was not merely obliterated: it had been scorched and pulverised as if by an earthquake, stamped flat and heaved up again, caught as it fell and blown all ways; and when the four minutes’ blast of destruction moved on, was left dissolved into its elements, heaped in fantastic mounds of mud, or excavated into crumbling pits already half full of water… The great trouble at first was to find our right direction, for all our famous groups of trees were still invisible, and Kitchener’s Wood was veiled completely by the smoke and dust of the barrage. The German trenches which we had studied on the map were blown to pieces and unrecognisable. One could see nothing anywhere, in fact, but a brown waste of mud blasted into ridges and hollows …2

Slow progress made them late to the first objective at Bosche Castle with the trench system in front of Kitchener’s Wood. They ran in to shellfire and lost their unditching beam as the tank plunged into a shell hole.

“I got my whole crew out to recover it; but to lift on to the roof again 9 cwt. of steel and wood in so unhandy a form was beyond our powers; and the occasion being urgent, I decided to abandon the thing rather than waste time in manoeuvring the tank and fixing the clamps or other tackle… We obtained a more comprehensive view of the outer world during this excursion, but there was little to be seen. The battlefield wore that melancholy and deserted air characteristic of modern war. Acres of foul slime below, dark and heavy clouds hanging low overhead, odours of gases and corruption, a few tree-stumps, a few bodies lying crumpled in the mud, half a dozen tanks labouring awkwardly in the middle distance, and the shell -bursts shooting upward like vast ephemeral mush-rooms — and that was all. There was hardly a sign of life in all that mournful and chilling landscape.”

It was near Kitchener’s Wood that G46 got bogged down after attempting to negotiate a way pass the network of water filled shell holes.

“The water rushed in through the tracks and sponson doors, covered the floor-boards, and flooded the sump: the fly-wheel thrashed through it for a second or two, sending showers about the interior; and then the tank, not having been constructed for submarine warfare, gave up the struggle. The engine raced with an increased but futile noise, for the wet clutch had ceased to grip, and we did not move. It was nearly six o’clock, and the rain had begun to fall. To take stock of the situation we had to climb out through the manhole in the roof, the water having risen to such a height above the floor that we could not use the sponson doors. Once outside, it was manifest that there was nothing to be done. The lost unditching beam would not have helped us with the clutch half under water.”

2 Lt. D.G.Browne struggled through mud and shell holes on foot in an attempt to reach his section commander Kessel and Lt.Merchant’s tank G45 which had ditched some 500 yards to his rear. He was told to evacuate his tank, but in accordance with orders to leave two men behind on guard. A hazardous duty which 2 Lt. D.G.Browne acknowledges:

“But the duty, never popular, was likely to be peculiarly dangerous in the Salient, on account of the persistent shelling to be expected there. Near Mousetrap Farm, a day or two later, four men were killed while guarding a couple of derelict tanks, after which the practice of leaving such guards east of the canal was abandoned … Under these circumstances, much as I disliked the prospect of remaining in here myself, I felt that I could not leave two of my crew alone there; and I determined, therefore, to form one of the guard.”

2nd Lt. D.G.Browne remained with his second driver Swain, the other six men struggled back to the Hill Top Farm HQ only to be ordered back to the tank! One man was hit on route but with the help of a second made it to a dressing post. The remaining four eventually reached G46 again around four in the afternoon. The crew of G46 sat it out through hours of incessant shelling until about mid-day on 1st August. After a useless visit from a salvage officer and in the absence of further orders, Browne and Merchant agreed to leave their tanks that afternoon and return to Frascati. They headed for the Wieltje-St Julien road, after eventually reaching Frascati they were taken from Reigersberg by lorry back to the La Lovie camp. It was after eight at night on 1st August 1917.

But what of gunner Robert Handley? Was he back at La Lovie, or somewhere out there, unlucky to have picked the short straw and been left guarding a tank? Was he in a tank of 19th or 21st company?

There is at least strong evidence to suggest that Robert Handley was in 21st Company. When he volunteered to join the “Heavy Branch”and was officially transferred on 25th Feb 1917 he was part of a small group of ex DCLI men who either due to wounding or sickness had been in the UK in late 1916:

95269 L.W.Baggott

95270 W.J.Gray

95271 A.Dean

95272 R.Handley

95273 H.Hunt

95274 H.Jones

95276 F.W.H Littlejohns

95277 H.A.Taylor

95278 C.Turner

95279 W.C.Trewin

95283 F.G. Burch

Gray, Hunt (real name Barratt), Littlejohns and Burch are all known to have been in 21st Company.

One task that fell to “G” Battalion HQ Staff immediately the facts were known was to create a “Battlegraph”, a chart summarising each tank’s progress and final state after the first day. Two versions exist, one as an appendix to “G” battalion’s War Diary and the other as an appendix to the Tanks Corps’ 1st Brigade War Diary. The latter having two additions about “direct hits” to tanks, but neither show the direct hits suffered by tanks after 31st July.

Battlegraph – G Battalion copy

Battlegraph – 1st Brigade copy

The “Battlegraphs” and contemporary maps allow tank narratives to be constructed. They name individual Tank Commanders, but full crew list, if they ever existed, have been lost. Neither do they fully corroborate 2nd Lt. D.G.Browne’s recollection that:

“Near Mousetrap Farm, a day or two later, four men were killed while guarding a couple of derelict tanks, after which the practice of leaving such guards east of the canal was abandoned …”

Only one tank is shown to have ditched near Mousetrap Farm, G6 “Grantham” of 19th Company. The “G” Battalion war diary entry for the 2nd August 1917 is brutally succinct: two abandoned tanks are hit, two 21st Coy men acting as guards are killed.

G Bn War Diary 1 -2 Aug 1917

G Bn War Diary 3 -4 Aug 1917

There are no detailed casualty lists naming individuals, just a summary which appears in an appendix to the Brigade war diary which was part of a report on the 31st July operations.

The only men killed on 31st July were the crew of 19 Company’s Tank “Glamorgan”. The figures include four casualties from 21st Company which must have occurred in the following days. Were these the four men alluded to by 2nd Lt. D.G.Browne and why does the “G” Battalion War Diary only mention two?

It is the work of the Imperial War Graves Commission that may hold the answer to the discrepancies in “G” Battalion’s records and explain Robert Handley’s fate. In its new guise as CWGC, the modern register and associated original casualty burial returns reveal the four names officially recorded as having lost their lives on 2nd August 1917:

EDWARDS, CHARLES WILLIAM

Rank: Gunner

Service No:70026

Date of Death:02/08/1917 Age:28

Regiment/Service:Tank Corps “G” Bn.

Grave Reference: IV. D. 19. Cemetery: ARTILLERY WOOD CEMETERY

Additional Information: Son of William Henry and Hannah Edwards.

MACCULLOCH, D

Rank: Gunner Service No:77524

Date of Death:02/08/1917 Age:32

Regiment/Service: Tank Corps “G” Bn.

Grave Reference: IV. D. 18. Cemetery: ARTILLERY WOOD CEMETERY

Additional Information: Son of John and Susan Macculloch, of 11E, London St., Edinburgh. Native of Oban, Argyll.

LITTLEJOHNS, F W H

Rank: Gunner

Service No: 95276

Date of Death: 02/08/1917

Regiment/Service: Tank Corps “G” Bn. Grave Reference: III. K. 25. Cemetery:

ESSEX FARM CEMETERY

HANDLEY, ROBERT

Rank: Private

Service No: 95272 Date of Death:02/08/1917Age:23

Regiment/Service: Tank Corps “G” Bn. Panel Reference: Panel 56.

Memorial: YPRES (MENIN GATE) MEMORIAL

Additional Information: Son of George William and Emma Handley, of 5, Heaton Rd., Mitcham, Surrey.

According to burial return documents dating from 1919, Edwards and McCulloch were originally found together at map location “c.8.c.5.5” in graves marked by crosses which clearly identified them as both members of 21st Company, “G” Battalion, Tanks Corps, and were dated 2/8/17. Could they have been the two men reported killed in the Battalion War Diary while guarding a tank? Perhaps, but the location of their original graves bears no relation to the known tank positions at the time and is far from the Mousetrap Farm mentioned by 2nd Lt. D.G.Browne. Although it is likely they were brought to a safer place to be buried.

Gunner Littlejohns is recorded as dying of wounds at Essex Farm, close to the Yser Canal’s western bank, used by dressing stations at the time. His family are believed to have received word that he was wounded before he died on the 2nd August 1917. The Battalion War Diary does state a 6-pdr gunner was wounded during gas shelling at Frascati on the night of 28 July and sent down to the CCS. If Francis William Henry Littlejohns was the casualty, it is possible he suffered from the delayed effects of mustard gas. Whatever the truth, there is one puzzling question about Gunner Littlejohns burial return. Why should his service number be incorrectly stated as that of Robert Handley’s?

The sad conclusion is that the inconsistent and incomplete record keeping of “G” Battalion make it impossible to say with any certainty how and where Robert Handley lost his life. The question of why Robert Handley’s service number should appear against Gunner Littlejohn’s burial return is likely never to be answered. The final insult to Robert Handley and the three others who died on 2nd August 1917, is the omission of their names from the “Roll of Honour” which appears as an appendix to the war dairy entitled “A Brief Battle-History of the 7th Battalion” and dated December 1918. It is a prototype for the slender 35 page publication of 1919.

G Bn Roll of Honour – Dec 1918

G Bn Roll of Honour – Dec 1918

Mitcham’s Tank Man, Robert Handley had simply been forgotten. Ultimately where and how Robert Handley had met his end may have been of little consequence to the Handley family at Heaton Road, Mitcham. All they knew was a son and brother would never return. They ensured Robert’s name appears on the Civic Memorial at Lower Green, and on the wooden memorial panel at their local St.Barnabas Church.

© Copyright John Salmon